Baptism No Church Ordinance

- brandon corley

- Dec 11, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 12, 2025

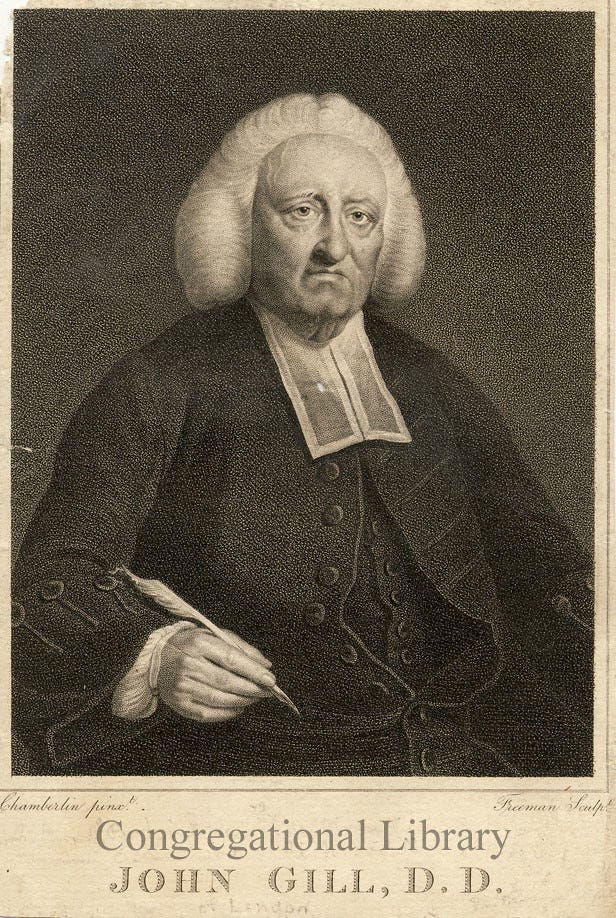

I thought it would be helpful to make a short post explaining my understanding of the early Baptist view on baptism not being a church ordinance as I have noticed that Gill's view on this appears to cause confusion and I have yet to come across an exposition of him that I think to be correct even though I think his view relatively clear. The relevant section of Gill is as follows:

As the first covenant, or testament, had ordinances of divine service, which are shaken, removed, and abolished; so the New Testament, or gospel dispensation, has ordinances of divine worship, which cannot be shaken, but will remain until the second coming of Christ: these, as Austin says, are few; and easy to be observed, and of a very expressive signification. Among which, baptism must be reckoned one, and is proper to be treated of in the first place; for though it is not a church ordinance, it is an ordinance of God, and a part and branch of public worship. When I say it is not a church ordinance, I mean it is not an ordinance administered in the church, but out of it, and in order to admission into it, and communion with it; it is preparatory to it, and a qualification for it; it does not make a person a member of a church, or admit him into a visible church; persons must first be baptized, and then added to the church, as the three thousand converts were; a church has nothing to do with the baptism of any, but to be satisfied they are baptized before they are admitted into communion with it. Admission to baptism lies solely in the breast of the administrator, who is the only judge of qualifications for it, and has the sole power of receiving to it, and of rejecting from it; if nor satisfied, he may reject a person thought fit by a church, and admit a person to baptism not thought fit by a church; but a disagreement is not desirable nor advisable: the orderly, regular, scriptural rule of proceeding seems to be this: a person inclined to submit to baptism, and to join in communion with a church, should first apply to an administrator; and upon giving him satisfaction, be baptized by him; and then should propose to the church for communion... (https://ccel.org/ccel/gill/practical/practical.iv.i.html)

In explaining the logic behind this view (and why I think it to be by no means the uncommon view among the early Baptists), I want to first point out a very underappreciated point of difference between the early Baptists and the Paedobaptists, namely, who is qualified to administer baptism. The standard Reformed Paedobaptist answer is that (at least in ordinary circumstances) only teaching elders may administer baptism (see various sources here and here; see here against those who held the office of teacher administering, and here against ruling elders). In fact, so far as I have been able to tell (though I will not take the time to prove this here), this position is held so strongly by the generality of Reformed Paedobaptists that not only is the lawfulness of such baptisms denied, but also their validity (see Turretin on baptisms by laity, Beza, the French churches; as best I can tell, the Paedobaptists think the form of the sacrament only able to be conferred by one holding office; this I have argued against here).

The 1LBCF (I quote the 1646 because it is clearer than the 1644 here), XLI interestingly takes a clear side on the question, affirming the view that the administration of baptism isn’t limited to teaching elders, but belongs to all “disciples” (which includes gifted brothers):

“The persons designed by Christ, to dispense this ordinance, the Scriptures hold forth to a preaching Disciple, it being no where tied to a particular church, officer, or person extraordinarily sent, the commission enjoining the administration, being given to them under no other consideration, but as considered Disciples.”

On this, see Edification and Beauty, 140-141. A "preaching disciple," refers to anyone with commission to preach the gospel and thus would include not only elders (whether teaching or ruling) and teachers but also gifted brothers. Henry Jessey in his Storehouse of Provision, pages 57-65 and 89-92 expounds this view very clearly, arguing from Matthew 28:16-20 that the Great Commission was given to the apostles not as apostles or as elders, but as “preaching disciples.” Jessey's work contains the most thorough explanation of the Baptist opinion on this matter that I know of.

So, with this context in mind, when we come John Gill’s view:

“Admission to baptism lies solely in the breast of the administrator, who is the only judge of qualifications for it, and has the sole power of receiving to it, and of rejecting from it; if nor satisfied, he may reject a person thought fit by a church, and admit a person to baptism not thought fit by a church; but a disagreement is not desirable nor advisable”

While it’s been suggested that Gill’s view is at odds with congregationalism, I think this misses Gill’s point in that he thinks baptism is not a “church ordinance” albeit it is still an ordinance of God. If he admitted it was a church ordinance, then there would be difficulty. But I think that what Gill is doing is actually just understanding baptism in line with 1LBCF as an ordinance given to “[preaching] Disciples” and so not an ordinance tied to the execution of the key of authority within a local church (which I think is why 1LBCF says baptism is “not tied to a particular church, officer…”). Baptism is not an ordinance proper to any church office, nor to any church. Rather, it is an ordinance of the Gospel given to all preaching disciples. Thus, authority for the administration of baptism lies solely in the preaching disciple and is his sole prerogative to administer since as an ordinance it hasn’t been given to churches or church officers as such (although, of course, for good order, the administer should confer with his local church as Gill explains).

Comments